if you can make it to the Hornblll festival in Nagaland this month, great. But if you can’t, no issues. You can always go later and do the state on a motorcycle, writes Shahwar Hussain

This is the third time in as many visits to the Kohima War Cemetery that lye seen the same old man -and always at the same stone bench. But I never made an attempt to speak to him because I didn’t want to intrude. I guess he, like me, finds the cemetery a peaceful place to spend some time alone. Indeed, you’ll find all the solitude you need at the World War II Cemetery. But having been on the road for sometime, riding through a few states in North East India and making friends by the dozen, I thought this time it would be okay to intrude.

I walked up to say hello, and as he turned towards me with a warm smile, I noticed for the first time a row of shiny War Medals pinned to his shawl. He had fought against the invading Japanese army in the bitter Kohima War when he was all of 19 or so. The sun dipped over the mountain, and the skies turned a fiery red as he told me stories of heroism, pain, death and glory. Wowl Only a microscopic minority of my fellow travelers would have had the good luck to hear firsthand accounts from a war hero.

I was leading a few friends on a motorcycle tour of North East India and we tried to travel through the less frequented routes. As we left Dimapur, instead of the highway, we took a very long detour to Kohima. The detour took us to Peren town, to the villages of Nsong, Nthuma, across the Barak river on a wildly swinging ricketysusperisfon bridge and on to Tamenglong dlstr.rct, of Manipur, inside the Tharon Caves

- the hideout of the freedom fighter Rani Gaidinliu, on to the village of New Puilwa, Benereu, Ozulake and finally

to the historic village of Khonoma, These hidden trails are way off the tourist maps, and they certainly lead to wonderful places. That’s the fun of motorcycling through the backroads.

Along the way we met some really interesting people like the forest guard at Nthuma who helped us get to an Inspection Bungalow in the middle of the forest and gave us some Baja Mirchi chutneys that blew the roof of my mouth; the pickup truck driver who took us to the Tharon caves and insisted that we spend the night in his house on the way back. And how can I forget the generous and far sighted people of New Puilwa? With only one college graduate and no government servants, the villagers have shown amazing civic and environmental understanding. They have marked out a large area in the forest as Reserve Forest where no one from the village is allowed to hunt or fell trees. Khonoma village has a nice easy feeling to it. Cobbled streets, terrace cultivation below the village and the hills are thickly wooded. Khonoma has been named as a Green Village because of its successful environment conservation projects. The village attracts birdwatchers by the dozens. unfortunately we couldn’t trek up to the beautiful Dzukou Valley.

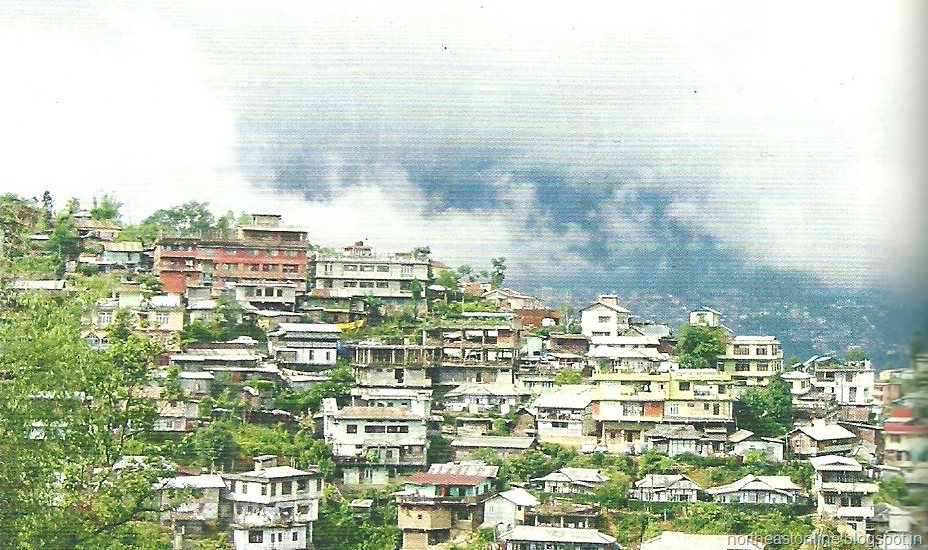

In another era, the villagers of Khonoma had fought pitched battles against the invading British forces and later on against the Japanese army in WW II. The remains of the forts used against the British are still there. They look rather flimsy now but all those years back, with dense jungles all around, the British must have found them rather tough to get to Kohima and Khonoma are just 20 km apart, but there’s a world of difference. From the easy pace of the village, the call of the birds, clean cobbled street, and the wide open vistas, we were transported to a relatively big city, and all its sights, in the span of just an hour A couple of days in Kohima and we rode off to Wokha and Mon. The 30 km ride to Wokha took more time than it should as we stopped every few kilometres to shoot pictures.

We halted at Longsa village at a friend’s house - a much better place to spend the night than a tourist lodge and the kitchen doesn’t close at 9 pm. The next night was even better as

we camped at an island in the Doyang reservoir A hydro-electricity project across the Doyang river has flooded an area of more than 8000 hectares. There are small islands all over the reservoir, where the local fishermen have made their huts. And one such fisherman, named Andrew Ezung, invited us to stay over the night in his but.

After a 45-minute boat ride through stretches with dead trees sticking out of the water, we reached the hut. It was rather eerie, and after dark it was downright creepy. Along the way, Andrew pulled up a 5-kg fish from the net which he had laid in the morning, and also shot a crane with a .22 rifle. Well, we had enough for dinner

Later at night, I lay outside my tent with a million stars above me, and the only sound heard was the soft lapping of the water against the two country boats by the shore. It was peaceful, and if I was on my own I would certainly have stayed put for few more days.

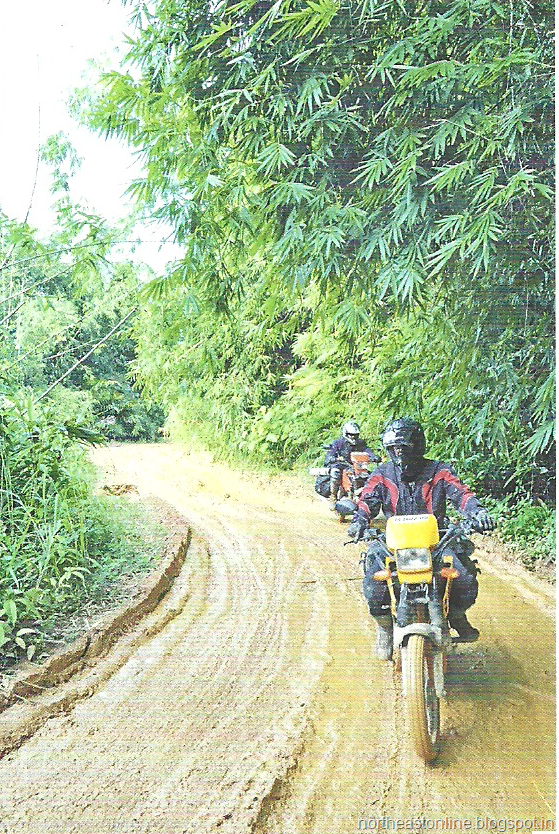

Another day and a half of riding and we reached Mon. the headquarter of the Konyak Nagas. The skies had promised rain all day long, and, as soon as we hit the hills, the heavens opened in earnest. It’s just 45 km to the town of Mon from the Assam border at Sonari, but it takes two hours to travel the distance. This stretch of road is being constructed, and there’s nothing but mud all the way The rain made the surface so slippery that, at downhill stretches, it was downright dangerous.

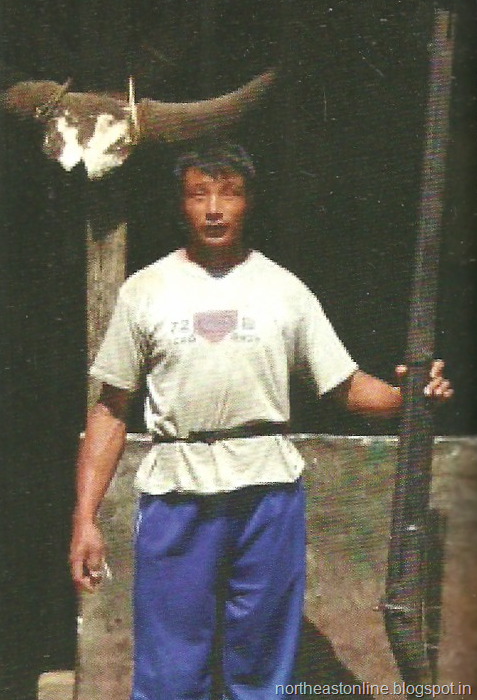

Next day, we rode for another 42 km from Mon tin a village called Lungwa. This village straddles the international border between India and Myanmar, and it seems to have been caught in a time warp. Almost all the houses in the village, except the schools and the church, are built in the traditional manner - with bamboo, wood, and leaves for roof. And the houses here are huge. As we sat inside the Angh’s (village chief’s) house, I realised that a two bedroom fiat would easily fit in his common room.

The Konyaks were the most feared headhunting warriors in all of Nagaland. And they’ve hunted heads in living memory. As we moved around the village, we saw a lot of tattooed old men, who were the warriors. For a Konyak warrior, getting a face tattoo was the ultimate honour. Any warrior who went into warfare was decorated with a ‘V shaped tattoo in his body. But if a warrior brings back the head of an enemy from the battle, he was decorated with tattoos on his face. The more heads he collected, the more intricate the tattoos grew - as did his status. And the tattoos were done by the Queen. Almost all the villages had their own collection of human skulls - trophies from battles fought in another era. The advent of Christianity resulted in most of these collections being buried, except for in some villages like Chenga Shengue, which has built a

museum to house the skulls, and other artefacts from that era.

The Konyaks are ruled by Anghs, and the Anghship is hereditary Although the Anghs might not be rich in monetary terms, they wield enormous power and control over the society. The Angh of Lungwa, whose house straddles the international border - half of his house lies in India, and the other halt in Myanmar - controls five villages on the Indian side, but has more than 30 villages under him inside Myanmar These villages pay their obedience, or taxes (if you want to call it that), to the Angh of Lungwa. Fire wood from the jungle, agricultural products, and meat are all delivered to the Angh in certain portions. They have been doing this for ages, and they have no regard for a manmade border. In fact, many villagers from Lungwa are employed as soldiers in Myanmar’s army

The Konyaks are master craftsmen. They make excellent artefacts, out of bones, wood and metal. They make fabulous muzzle loading flintlock rifles and pistols just like the ones that Robinson Crusoe used against the pirates. And they produce their own gunpowder too. Rut, it’s a pity that we can’t get them to mainland India without a license.

We were in time for the last couple of days of the Aoling festival and what an interesting festival it is. The air was filled with war cries as the Konyak warriors fought mock battles complete with gunfire and fights with spears and machetes. It is all quite dramatic as smoke from the ancient guns fill the air and the warriors come charging out of the smoke. The Aoling festival (April 1 to 6) relives the headhunting days of the Konyak and is a must see.

The North east is a hotbed of culture and tradition and it is best to travel with an open mind without any preconceived notions. Carry cash or at the most, some traveller’s cheques. Credit cards arejust pieces of four inch coloured plastics.

Visit these places before ‘civilization’ pollutes them, You wouldn’t want to see a McDonald outlet in the middle of the jungle, would you?

0 comments:

Post a Comment